May 29, 2016 – Bulach, Switzerland

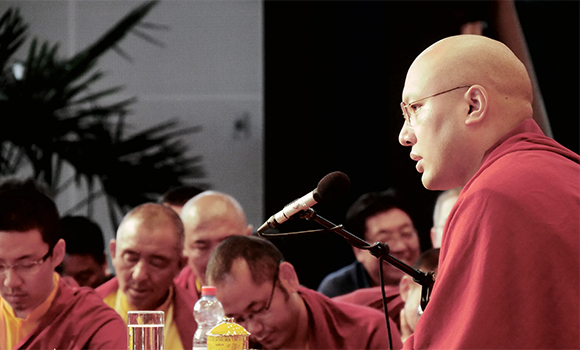

The Karmapa sat on stage in a comfortable armchair covered in red and gold brocade for this final session, held on his last afternoon in Switzerland.

He began by recollecting his own childhood in a remote area of Tibet, devoid of modern technology and other aspects of the contemporary world. Within this very traditional culture, the natural world was viewed as sacred and treated with great respect. People thought the mountains and other places were living systems and home to many deities. There was no plastic garbage and no need for rubbish bins as everything was organic and biodegradable. Consequently, when plastic wrappings finally arrived, the people would just throw them away because they were unaware that plastic did not biodegrade. Home life was simple. Everything they owned had a use in daily life and there was no television or the like.

“What I saw in this Tibetan culture was the principle of being happy and content with little,” His Holiness commented. “To be content with little and have few wants is an important practice in Buddhism.”

He went on to explain how this was especially true for monks and nuns. In Tibetan, the Karmapa explained, the words for a fully ordained monk gelong and a fully ordained nun gelongma are made up of two words. Ge [Tib. dge] means “virtuous” and longwa [Tib. Slong ba] means “beggar,” so in Tibetan, a bhikshu or a bhikshuni is a “virtuous beggar.” They hold the highest vows, His Holiness observed, and their fundamental practice is to be content and live with few desires and few things. Traditionally, if a monk’s robes were torn, they were patched, and when they were too tattered to be worn, they would be washed and used as rags, and finally when they could no longer be used as rags, they would be added into the making of bricks. Nothing was ever wasted. It was also forbidden for monks and nuns to have personal belongings. This is how the Buddha and his sangha lived, similar to modern day socialism.

The Buddha was first to introduce an administration for the sangha, and later in the tradition, came the large monastic universities such as Nalanda and Vikramashila. These were the first universities in the world, and had rules for administration and finance. However, kings and laypeople brought offerings, which created a problem, as the monks were not allowed to own things. So the monasteries built special treasuries to store the offerings. When armies invaded India, they first attacked the monasteries, destroyed them and took these treasuries.

The Karmapa then linked the question of living with less to the question of the environment: “I want to talk about living with less and being content as a way to protect the environment,” he stated.

Science had provided much information about the environmental crisis, he continued, but knowledge in and of itself was not enough. The crux of the matter was how to transform knowledge into action.

The Karmapa made several recommendations. First, environmental scientists could confer and work together with religious leaders on ways to protect the environment. Second, we each should make an honest assessment of our daily life and its impact on the environment so that we can change how we live in order to protect the environment. Third, as motivation is key, we all need to develop our motivation, so that it becomes stronger.

Information, statistics and knowledge engage our intellects but do not necessarily bring about a change of heart or a change in behaviour, he remarked. Warnings and graphic images on cigarette packets, for example, have not deterred smokers. Ignorance in human beings is so strong that often we do not recognise the way things really are.

Fourth, we must develop inner contentment, which His Holiness described as “a natural resource.” When we are content, we feel that we have everything needed. Learning to be content is more important than having fewer desires, he explained, because without contentment we will never feel satisfied: we will always have unfilled desires and the feeling that we lack something.

Returning to a theme of previous talks, the Karmapa suggested how we could develop contentment through meditation practice. Resting our awareness on the breath, we focus on the present moment, not chasing after memories from the past or speculating about the future. Through practices such as this, inner contentment can grow progressively. Sometimes when we feel a little helpless, or think we lack something, or feel lost, if we remember to focus on our breath, we can experience happiness. In addition, concentrating on the breath reminds us of our interdependence with the environment and the plants that provide us with the oxygen we need. Breathing can become something wondrous.

However, because of our constant desires, our mind and body cannot find peace. “At some point, we have to say enough is enough,” His Holiness advised, because desires can be limitless, and if we have strong desires, we will be unable to find contentment. Ultimately, we have to take a further step and turn our back on our desires and let go of attachment. This is renunciation.

The principle of renunciation entails rejecting the social constructs of the society in which we live. His Holiness pointed to an example from New Delhi in India. When he came to India in 2000, there were far fewer cars on the road but now there are traffic jams everywhere and the air is much polluted. A major part of the problem is the more than five million private cars and it is exacerbated by the addition of between 4000 – 5000 new cars every day. His Holiness recounted how he had once asked a Tibetan driver why there were so many cars, and the driver replied, “When your neighbour buys a car, you have to buy a car as well.”

“This is the situation today,” His Holiness commented.

- Instead of using our own intelligence and wisdom, under the power of ignorance, we just follow what other people do. We are under the influence of external factors and circumstances that determine our lives. When we talk about renunciation and letting go of desire, it means that we are no longer under these influences, but have the intelligence and wisdom to choose our own way.

We need to recognize that what society presents as real is more like a lie, he continued, and then we can take our own way.

In the end, the issue is taking responsibility for our actions. If we buy a car, that is our decision, but that decision has consequences. When we drive that car on the road we add to air pollution, traffic jams and so on. We cannot avoid living in society and we should live in harmony with everyone, but it is paramount that we know the correct way to act.

The Karmapa then opened up the floor to questions.

The first one asked his advice on practical solutions to protect the environment, including vegetarianism. When shopping, we should not just think of what we want as individuals, but how our purchases affect the environment. With regard to vegetarianism, as compassionate individuals we may want to give up eating meat or reduce the amount we eat, and this will have a positive effect on the environment.

The second question posed the dilemma of a vegetarian who has to buy and prepare meat for consumption by others.

His Holiness explained that during the Buddha’s time, the sangha was allowed to eat meat with certain restrictions such as the animal not being specially killed for them. If we have to prepare meat, there are mantras that can be recited or we can recite the names of the Buddhas. If we eat meat, it is good to make aspiration and dedication prayers for the animal that has died.

With the third question a student asked what to do when their root lama had died. Did they need to find another lama or could they continue to practise on the basis of that lama’s instructions?

His Holiness explained that there are different ways of receiving the Dharma, and it is possible to have different lamas, sometimes from different transmission lineages. All the great masters who restored the teachings in Tibet were non-sectarian and received teachings from lamas of different traditions.

However, when we have different lamas there is a danger that we will become confused. Our root lama is the one with whom we have the strongest connection, and for whom we have the greatest devotion and affection. That root lama does not have to be a living lama. If we have deep devotion and a strong connection, we can continue to pray to our root lama after they have passed away. If we encounter difficulties in our practice, it is best to consult a living lama, but our root lama remains in our heart, and the connection with them continues.

Returning to the environmental theme, the next questioner asked the Karmapa’s opinion on whether the earth could recover if human beings were to change their behaviour.

“Hoping the earth will recover does not help much,” His Holiness began, “we must actually do something.” More natural catastrophes might be a wake-up call, but it is not easy to change our behaviour and attitudes. The environmental crisis is on a vast scale and it is difficult to change the situation overall. However, there is a Tibetan saying “Drop by drop the ocean is filled. Drop by drop a hole is made in the rock.” If we all work together, we can do something. If we wait upon the government, it could take a long time, so we have to make our own decision and take action.

We can choose to use things that are less harmful to the environment. If we change our way of consuming, the Karmapa suggested, we would be setting an example for others, and effect a change in their attitudes too.

In conclusion, His Holiness expressed his deep gratitude to all those who had worked to make this first visit to Switzerland such a success, and reiterated his hope of returning to Switzerland and also visiting other European countries in the future. He especially thanked Namkha Rinpoche and the Bureau of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Switzerland.

Lastly, the President of Rigdzin Switzerland, Andres Larrain, rose and responded with a speech of thanks to His Holiness, giving a history of the Karmapa’s visit and conveying everyone’s gratitude for the “inexpressible blessings” he had granted during his time in Switzerland.

The President’s words captured the experience of all those fortunate enough to attend the teachings: “You have taught us the depths of Buddhism, in a way that was at the same time profound, easy to understand, and with a sparkling sense of humour.”