Bonn, Germany – 28th August, 2015

Evening Session

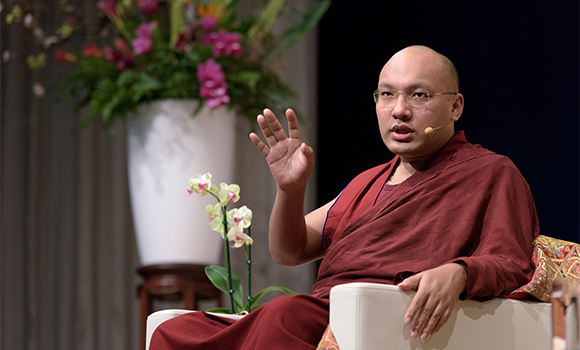

In the first public talk of his second visit to Europe, His Holiness the 17th Karmapa began by reiterating his hope that next time he might be able to visit more countries in Europe.

He admitted to growing very fond of Germany, and joked with his audience about the sound of the German language and the German breakfast which is like lunch. On a more serious note, he commented on the lusciousness of the German countryside and rejoiced in the effort Germans put into protecting the environment at all levels. However, he felt that there was a lot more that could still be done, and this would be the main topic for his discourse.

His own passion for helping the environment, he explained, stems from his early childhood experiences in Tibet. In that vast and ancient landscape, with a small population, the Tibetan people were able to fully enjoy the natural environment around them, and they regarded the elements of that environment– the lakes, mountains, rivers, meadows and so forth– as a living system, inhabited by gods and elemental spirits and endowed with a vibrant natural energy. Consequently, they held the natural environment in awe and treated it with deep respect. “This is the type of environment I grew up in,” His Holiness said, “and the habitual seeds are still strongly with me.” However, many people living in cities never have the opportunity to experience or enjoy nature directly. “When we are that distant from nature it becomes more difficult to have an appreciation of the natural beauty of nature and of how precious the natural environment is,” he reflected.

He then went on to consider the connection between Buddhism and the environment.

The 21st century is the age of information and discussion of environmental issues takes place across the spectrum of society: “Political parties express concern about the environment in response to available information, social activists do awareness raising, companies have taken note of environmental challenges, a lot of different people and different groups in the world are talking about the importance of the environment.” The challenge, however, is to translate talk into pragmatic action, and for this there needs to be a process in our mind-heart connection whereby the information we have in our brain brings about a change of heart which becomes the stepping stone for action. This is where the various spiritual traditions of the world have a part to play in protecting the environment. “Especially there is a role for Buddhism to be of benefit in protecting the environment and in trying to sustain the health of the environment. “

Throughout the life of Buddha himself, there is a strong environmental connection. His mother gave birth to him in a grove beside a tree; he achieved enlightenment under the Bodhi tree; he gave his first teaching in the Deer Park forest at Varanasi; and, according to the tradition, he attained parinirvana between two sal trees. Indeed, it was the natural environment which supported him in his attainment of enlightenment. To us the setting of his enlightenment may seem too mundane and unspectacular, “but because of that ordinariness he could connect with the universe, with all sentient beings”. We might feel that this is rather disappointing; no applause, nothing grand or ostentatious marked this great achievement. “From the Buddha’s perspective the situation of his enlightenment was perfect. Our minds on the other hand are so disturbed by material desire that when it comes to dharma we’re pushed along by our usual habits and come to expect the dharma to be exciting for us. That leads us to have an attitude of spiritual materialism.”

The Buddha taught that all sentient beings are bound together in a mutually dependent connection, the Karmapa explained. In traditional Buddhist language, the outer environment in which all sentient beings exist is referred to as the ‘container’, and living beings are the ‘content’. “This metaphor from the Buddha’s teachings is a wonderful illustration that clearly highlights the mutually dependent relationship that sentient beings have with the world and each other,” he commented. In addition, the container is not seen as simply a material object but rather as a living entity that we must protect because if this outer container is damaged, what it contains will also be damaged or even lost.

Protecting the environment is not easy, but, in the final section of his talk, His Holiness detailed steps we can take ourselves in our own lives in order to protect it.

The first priority is to work on our own motivation and determination. We need to transform our own relationship with the environment and change our life-style, because that is where the problem lies. If we examine our habits closely, we may find we need to change them, and that can be painful and difficult. “We have a lot of information but information alone is not enough. We need to actually transform our motivation process so as to really genuinely transform our relationship with the environment; it’s important to work on our motivation.”

Next, we should challenge the culture of greed and in particular our own greed.

“It comes down to controlling our own greed,” he commented. “If we look at what’s coming at us from the media, television, and advertising and so forth, it is designed to increase our greed. If we want to control or reduce our greed we need to take on the responsibility for ourselves – others won’t do it for us. We need to look into the distinction between what we really need and what we simply want. “

But this too depends on being motivated and determined: “We need great strength of heart, great resolve. Without that, we won’t be able to be decisive, and if we’re not decisive we won’t be able to make changes.”

Recognising the danger of ‘saying too much and doing too little’, His Holiness brought his teaching to an end with a final word of advice on how we as individuals can protect the environment. We can begin by making small changes, he suggested, on a day-to-day basis, according to what we are able to do. Then, over time, “our actions will accumulate like drops of water, drop after drop, and we’ll definitely contribute to a positive change.”