(March 26, 2015 – Cambridge, Massachusetts)

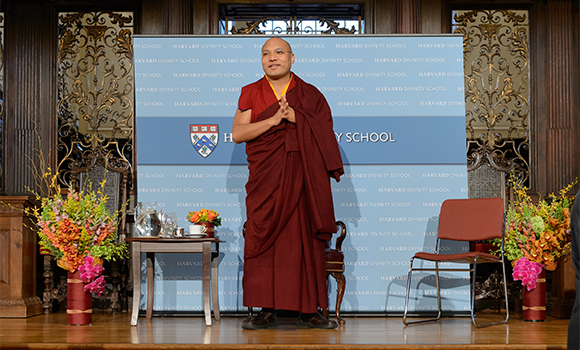

The spacious interior of Harvard’s Memorial Chapel quietly filled with students, faculty and special guests. Light was streaming in through the tall, arched windows and played off the delicate filigree of the altar gates. In front them an elegant chair had been set up for His Holiness the Karmapa, who appeared right on time, moving easily across the small stage to the waiting chair. This lama with the 900-year-old lineage is now present at the 350-year-old university, the oldest institution of higher learning in the US.

Professor David Hempton, the Dean of the Faculty of Divinity, welcomed the Karmapa with warm words and the gift of a silver memorial bowl inscribed to him “with highest appreciation on the occasion of his historic visit to the Harvard Divinity School.” Professor Hempton recalled that the 16th Karmapa had come to the Harvard Divinity School in 1976, and that now the Divinity School hosted a thriving Buddhist studies and ministry program.

Next Professor Janet Gyatso, Associate Dean and the Hershey Professor of Buddhist Studies, introduced the Karmapa as the great hero—a reference to him as bodhisattva (literally “hero of full awakening”). She explained that the Karmapa was the first officially recognized reincarnating lama, or tulku, and then gave a swift history of the main incarnations of the Karmapa down to the present 17th one, Orgyen Trinley Dorje. She noted that the 17th Karmapa is no less exceptional than any of his predecessors, proof that the tulku system in Tibet is alive and well. Professor Gyatso characterized him as bold and intelligent with amazingly honest energy, pursuing his interests beyond traditional areas of study to include the environment, the status of women and social justice. She concluded by saying that his recent commitment to convene a platform for ordaining women in the monastic tradition followed by Tibetan Buddhists is of historical importance.

In his address to the assembly, the Karmapa began by making a link to his previous incarnation, the 16th Karmapa, who was one of the first masters to bring Tibetan Buddhism to US and came to Harvard. He was glad to be back, His Holiness said. Turning to the topic of how to care for living beings on the earth in this 21st century, he began by stating that the real essence of Buddhist teachings is dependent arising: all things arise by depending one upon the other. It is vital that we do not leave this a mere abstract philosophical idea, but apply it directly to our lives, he said. “How can I embody dependent arising? How do I know it through my emotional life? In this twenty-first century, we can all see that through social media and the Internet, interdependence is even more obvious, but the mere exchange of information is not enough. From one point of view, the more information we have, the clearer things become. On the other hand, sometimes we have too much information and it obscures, preventing us from truly understanding. Furthermore, interdependence is not just about sharing information or our thoughts among ourselves, but sharing the feelings we have in our hearts, our real experience.”

Following his own advice, the Karmapa related a story from his own life, when he was three or four years old and living with his nomad family. Their main food was meat, and so animals had to be killed in the autumn. “I remember clearly,” he said, “that I could not endure this. I still remember the unbearable feeling in my heart. I don’t know if you could call it compassion as described in the texts with precise definitions, but it was a feeling of great love in my heart.

“When I was young, I had no education, but I did have this natural feeling of sorrow and compassion. Then I was recognized as the Karmapa and put on a throne, but when I think back to the genuine, unfabricated feeling I had as a child, in some ways it surpasses the compassion I can have now. I really appreciate the compassion I had then. Children, especially young ones, have an innate capacity for genuine love and kindness. We can see that when one child is crying, another starts crying too, because they recognize the feeling and naturally sympathize with it. In this way our sympathy can extend to all living beings. This does not have to do with whether we recognize ourselves as spiritual or not; it is an inborn part of being human.

“As we grow up, our circumstances change and this can obscure our innate compassion. We are born with our compassion button switched on and then the button is switched off. As adults compassion does not come so easily to us. When we could take care of others, we think about ourselves: Will this harm me? How will it affect me? As we grow older, we become educated and, therefore, careful: even clever. We hesitate and worry about risks, so we lose our sense of connection. All of this obscures our innate compassion.

“Compassion is not a thought, but a feeling, which cannot be inculcated or encouraged. Compassion is something each of us has to volunteer through our natural courage and benevolence, which is the root of compassion.

“Dependent arising is a concept but it must become more than that. It has to be something we actually experience. We need to recognize that the environment and all the beings who inhabit it arise in dependence one upon the other, and further, that individual beings are also interdependent. The food we eat, the clothes we wear, and air we breathe has all come about through others. We cannot survive independently. The more keenly we feel this, the more we will feel that others’ well-being, their happiness and suffering, is very much a part of our own. This awareness will help us to take responsibility for others. And not just begin to take responsibility, but come to feel within us a compassion that is genuinely courageous.”

The Karmapa continued to comment on our present-day situation. “These days we are made extremely comfortable by the way we do things, but this also conceals a great deal from our sight, such as the process that culminates in the meat we eat. We lose the awareness of our connection to things and so there is a great need to deepen our awareness of our interdependence.

In conclusion, the Karmapa said that he wanted to leave the audience with one thought. “When we talk about disasters in this world, we usually think of things like epidemics and famine, but there is one source of disaster that we often fail to recognize—a lack of love. Due to this people have no help when they need it or no friends when friends are wanted. In a sense the most dangerous thing in this world is apathy. We think of weapons, warfare or disease as terrible dangers, and indeed they are, but once apathy takes hold of our mind, we can no longer avoid it.

“I urge you to feel a love that is courageous. Not in the sense of a grudging undertaking of a heavy burden in feeling responsible for the welfare of others, but a joyous acknowledgment of your interdependence with each and every other living being and with this environment.”