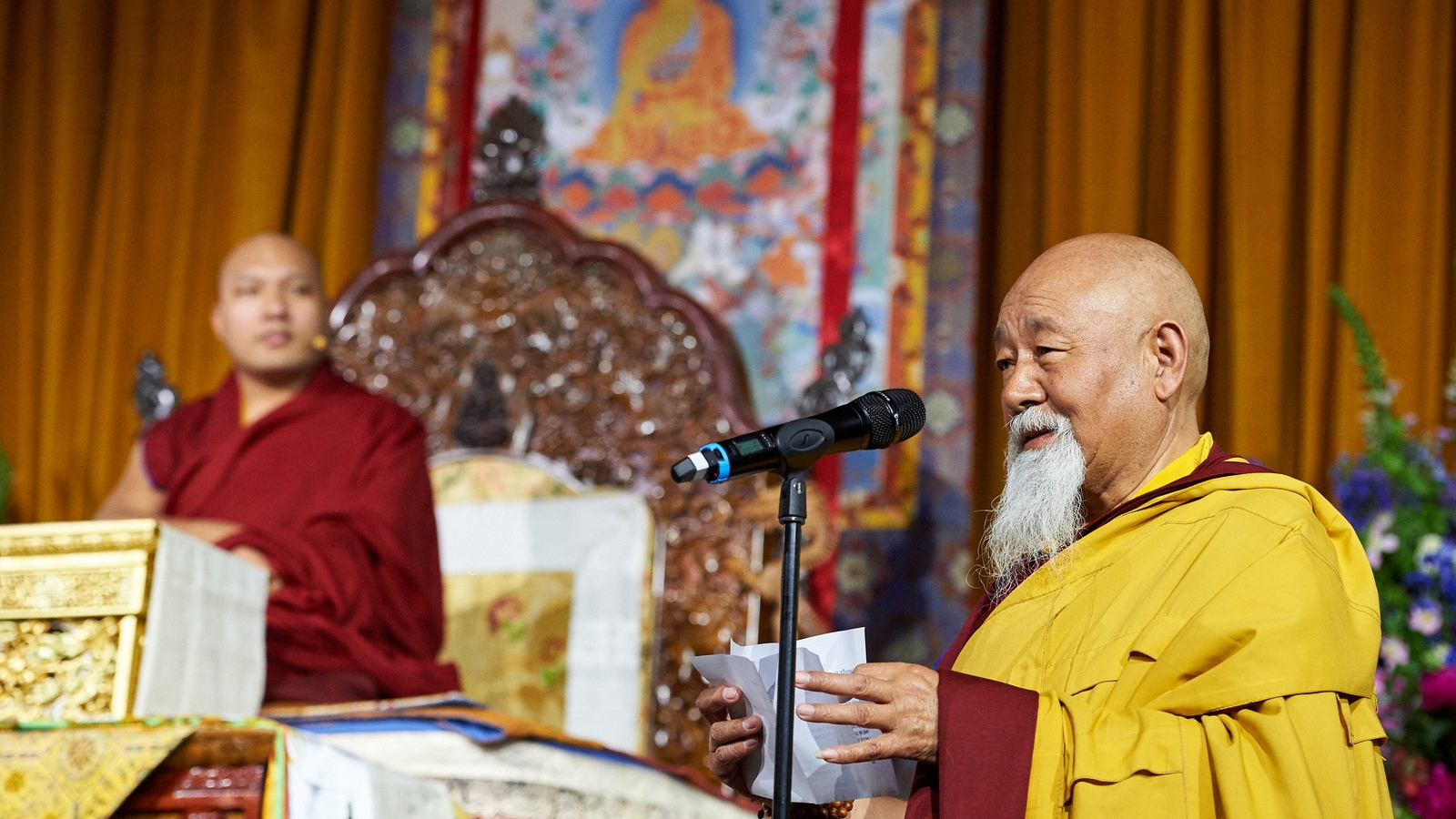

May 20, 2107 – Battersea Park, London, England

Reprising his teachings on the Eight Verses of Mind Training, the Karmapa turned to the second verse:

Wherever I am, whomever I’m with,May I regard myself as lower than all others,

And from the depths of my heart,

May I hold them as supreme and cherish them.

The first verse, he reminded us, gave the practice of seeing all living beings to be as precious as a wish-fulfilling jewel, and this second one encourages us always to be respectful towards others. Whomever we meet in whatever place, we train in respecting them and regarding ourselves as inferior, not in a superficial way, but from the depths of our hearts and the marrow of our bones. “This is about being humble,” the Karmapa remarked, “and mainly functions as an antidote to pride.” It is important, “because as we seek to benefit others, we will connect with all kinds of people, educated or not, wealthy or poor and we need to make our minds ready to be free of pride in any of these circumstances.”

To illustrate his point, the Karmapa gave the example of the powerful and vast oceans, which cover a good deal of the planet and still hold the lowest place, allowing all the rivers to flow into them. If they were elevated, the oceans would drain dry. Similarly, if we train ourselves in humility, anyone we meet becomes an opportunity for this practice, and virtuous qualities will naturally flow into us.

To illustrate pride, the opposite of humility, the Karmapa gave the example of pouring water on a ball. When we are puffed up with ourselves, there is no space for improvement, which we deem unnecessary, so it is very difficult to increase positive qualities as we miss the chances. Being humble, holding the lower place, opens up a pathway through which we can learn more and develop.

“Sometimes,” the Karmapa noted, “we confuse pride and confidence. The pride we are discussing here is something we should lose. It is a state of mind in which we focus on our own positive qualities and accomplishments to justify a sense of superiority and looking down on others. This is not an authentic way of practice because the qualities we focus on are not what they seem to be; they are not a true basis for having such an attitude. Actually they just fill our minds with clutter and keep our positive qualities from blossoming.”

The Karmapa explained further, “For bodhisattvas there is no end to learning, no state which they achieve and then are told, ‘You’ve completed your training. There is no higher state than this.’ The reason is that there is something to learn from each and every living being. When bodhisattvas are helping others, they learn from every being with whom they make a connection. And living beings are limitless. If there were only one of them to help, there would be no opportunity for inexhaustible learning. Living beings, however, are inexhaustible in number, so there is no end to training in the conduct of a bodhisattva.”

“Therefore, when we are encouraged to regard ourselves as lower than all others,” the Karmapa summarized, “it does not mean that we denigrate ourselves and jettison our self-esteem. In Buddhism, that would be considered a type of laziness called the laziness of self-deprecation. We cannot evade helping others with the excuse that we are not able. Regarding ourselves as lower than others is actually an opportunity to learn, since those we meet can educate us. Bodhisattvas have the motivation to learn something from everyone they meet, so their training has no end, just like living beings.”

The Karmapa then read the third verse:< In all activities I will examine my mind stream.

Since mental afflictions damage myself and others,

The moment they arise,

May I energetically face and reverse them.

He explained, “Whatever we might be doing—going somewhere, sitting down, falling sleep, and so forth—we should examine our streaming mind. When we notice negative emotions, we should try with all our energy to stop them the very instant they arise. This verse teaches being attentive and mindful as the antidote to afflictions. We are continually vigilant to what is happening in our minds, whether we are relaxing, driving, or facebooking.”

The Karmapa commented that these days many people conflate Buddhism with relaxation, turning it into a kind of “spiritual massage.” But this is not mind training, which actually requires intensive care and serious effort like a full workout at the gym. “Mind training resembles a series of exercises for our hearts and minds, and not simply relaxation,” he said. “Our habits and emotions run deep and some are negative, so they are not that easily altered. The process of changing bad habits and getting into new and more constructive ones is not that easy. It entails work and experiencing the feeling of being sore as if we had engaged in hard physical labor.”

Offering his advice, the Karmapa counseled, “We need to have a plan in place for how we will deal with any given situation. If we let the mind go where it wants to go, it will turn stubborn. There is a saying in Tibetan: ‘Appearances are skilled at deception and the mind is like a small child following after them.’ Instead of letting mind be fooled by appearances, we should take care of it like a small child, not letting it do whatever it wants; rather, we should examine carefully to discover the state of our mind.

“The great Kadampa masters of the past used games in training their minds. To play a game of mindfulness, they carried black and white stones to count the times they won or lost against their afflictions. Looking at the win-loss ratio was a way to get into positive habits. We must continually examine our minds since change will not happen by merely wishing things to be so. We need to put continued effort into seeing our mind clearly.”

The fourth verse reads:

Whenever I see beings of ill character

Weighed down by harsh misdeeds and suffering,

As if I had discovered a treasury of precious jewels,

May I cherish them as something difficult to find.

The verse advocates the practice of compassion in learning to cherish three types of living beings: those with difficult personalities, those weighed down by deep suffering, and those in the process of committing negative actions, big mistakes, or harmful activity. The Karmapa explained, “We should see each of these three types of individuals as an opportunity to put our compassion to use, thereby improving and making it more all-encompassing. This point is easy to understand but very difficult to put into practice.”

The Karmapa then left the remaining verses for the next day and responded to written questions.

Q: Do you talk to birds in this lifetime? What do they say?

A: “I phone them sometimes” the Karmapa replied in jest. “When I was young at Tsurphu, people said to me, ‘The Sixteenth Karmapa liked birds, so you must like them too,’ and they gave me many. Actually, I have no special connection with birds. To be honest, I was uncomfortable with keeping birds in cages. They are happier being free to fly around in nature. And maybe I sensed that it would mean that I, too, would be caged. It is better to leave them in their natural environment.”

Q: I have been practicing Dharma for more than forty years and was expecting the world to be better toward the end of my life. Could you explain where I went wrong?

A: “It is difficult to make the whole world a better place, and sometimes our hopes for how things might be are too big. If we scale down and work with ourselves so that we become good people, then there would be one more good person in the world and one less bad one.

“Sometimes the way we feel depends on what we are looking at. We could reflect on the state of the world and begin to lose hope. On the other hand, we could see one person practicing compassion or having a good heart, and that could encourage and inspire us.

“I read a digital newspaper with a good news section but it’s not updated nearly as much as the parts with mostly discouraging news. It is the shocking news that gets reposted but this does not mean that nothing positive is happening; we just do not hear about it. In the end, however, it comes down to us working on ourselves. This is where we start to make the world a better place.”

Q: How to deal with racial discrimination?

A: “It is essential to start by focusing on our commonalities, that we all are human beings seeking happiness and wishing to avoid suffering. From this perspective, we can develop love and compassion, which remove the labels that distance us from each other. We can then find mutual respect, affection, and a sense of equality. If we can begin from here, we can become closer, increasing our respect and love for each other. Inwardly, the more we connect with our own love and compassion, the more we will be able to connect with others.”

On this positive note, the question and answer session drew to a close. After the teaching, following through on the theme of connection, groups of disciples from individual countries were arranged, and the Karmapa moved from one to another, sitting down with people to take their questions and standing to receive their khatas. Finally he donned the yellow knit shirt of the volunteers and posed with them lined up on the stairs for a final photograph.