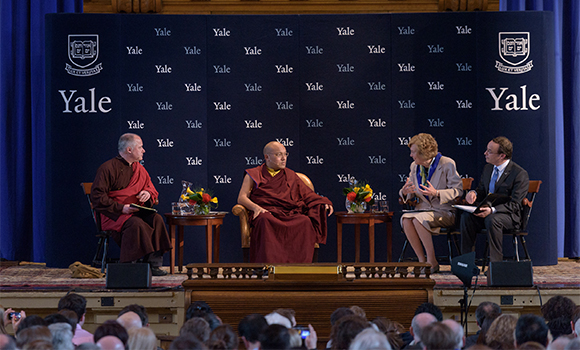

(April 7, 2015 – New Haven, Connecticut) On his second day at Yale, the Karmapa delivered the Chubb Fellowship Lecture, entitled, “Compassion in Action: Buddhism and the Environment.” This prestigious lecture was given in Woolsey Hall, an elegant space filled with the 2,500 people fortunate to have tickets. The front of the hall was filled with soaring organ pipes while two large screens flanked the Karmapa’s chair, set before a wide backdrop of indigo blue.

The Karmapa was first warmly welcomed by Jeffrey Brenzel, who is the master of Yale’s Timothy Dwight College, the official steward of the Chubb Fellowship. He listed the other sponsors of the Karmapa’s visit, which reflect the richness and diversity of Yale’s approach to the environment and its preservation: Yale Himalaya Initiative, the Forum on Religion and Ecology, the Department of Religious Studies, the School of Forestry and Environmental Studies, Yale Divinity School and the Macmillan School for International and Area Studies. Prof. Brenzel commended the Karmapa for making himself “astonishingly available, putting forth effort to meet, greet and connect with people while here.”

Andrew Quintman of the Department of Religious Studies introduced the Karmapa with a brief history of his lineage of reincarnations (tulkus), noting that the Karmapas are the first in the world to have this tradition in which a previous incarnation recognizes a subsequent one. “Now at the age of twenty-nine, the Karmapa is already recognized as a leading religious figure of his generation and an accomplished Buddhist teacher.” He is a prolific artist, a religious reformer, a social activist and an environmentalist.

To illustrate the Karmapa’s heart-felt involvement, Professor Quintman quoted him: “Whatever it is that I do, I want it to have a long-term visible impact and for it to be practical. If I have the opportunity, I would most like to restore the natural environment in the Himalayas and Tibet, and to especially protect the forests, the water and the wildlife of this region.”

Professor Quintman predicted, “This 17th Karmapa will revolutionize Buddhism, not just in Tibet but on a global scale.”

The Karmapa began talking about the environment by speaking of his personal experience and what inspired him to get involved in protecting the environment. He was born in an isolated, pristine part of Eastern Tibet, untouched by modern development, where he lived until seven years old. This world was all that he knew, so as a child he had a special connection with his surroundings, a feeling that he remembers to this day. It is on the basis of this experience that he sustains his wish to protect the environment.

The Karmapa continued to explain that when he was young, the people he knew respected the environment as a living system to be protected: the mountains, the sources of water and other special places were regarded as an interconnected, living world and as dwelling places of spirits. “We respected every aspect of the environment as part of a living system; for example, we did not wash our clothes or our hands in running water. Everything was regarded as innately sacred.”

The Karmapa then emphasized the importance of recognizing that we are all interdependent: “To understand the necessity of environmental protection, we need to understand how connected we are to each other and to the environment.” We can see our relatedness if we think about how we are sustained through food, air and clothing, all of which come to us through a vast network of interdependent links. We do not see this situation because we tend to divide the world into outer and inner: the environment is out there and we are in here.” The Karmapa counseled that we need to decrease this sense of distance between subject and object and finally dissolve the boundary. If we can do this, we will “discover a sense of closeness and see how connected we are to the environment. Buddhism refers to the external environment and the living beings inhabiting it as the container and the contained: We are all held by the environment and should come to acknowledge that interrelationship.”

Throughout his lecture, the Karmapa emphasized how important it is to become personally involved. Understanding is not enough: We must open our hearts and become engaged. He observed, “We tend to separate ourselves as persons from our knowledge. If we know the need for environmental protection, we should apply it in our daily lives. It has to become so intimate to our being that we feel it in our hearts and it changes our behavior.”

Since it touches our hearts and minds, a spiritual path can inspire us to engage in environmental stewardship. The Karmapa explained, “Every religion in the world can play its part. If we work together and apply the knowledge that world religions and numerous indigenous cultures have preserved, I’m confident that we will discover together that environmental protection is not just a science but a way of life.” He noted that here is a common foundation for spirituality and science: “If we base our environmental stewardship on being loving and kind, there is no difference between science and religion.”

The Karmapa then spoke of the Himalayan region and the Tibetan plateau; these glaciers are a treasury of water, the source of many great rivers of Asia. He said, “We have to be especially concerned with the environment in the Himalayan region and the conservation of water there. We are training the Himalayan monasteries in the best environmental practices so they can spread this information to their local communities.”

With this reference to community work, the Karmapa closed his Chubb lecture, which has ranged from working with our minds and motivations through to how to engage and sustain practical activity in the world. There followed a lively question and answer period.

One question asked: “What is it that moves us to overcome our hesitation and move into action?” The Karmapa replied, “The bridge is a type of compassion or courage, a willingness to engage the power of our mind. We have the capacity to decide that we will take responsibility for ourselves as individuals. We can move from a mere understanding to something more emotionally felt if we listen to the advice from our hearts.”

Another question was about science and religion. For many years, scientists have been speaking of climate change and the environment. Some say this is no longer an issue of science alone, but a world question and a dialogue of science and religion.

The Karmapa replied, “Conserving the environment is fundamentally a moral issue. Its degradation has been caused by human greed, exacerbated by the media and the advertising industry. As we all know, human desire is limitless and environmental resources are limited. Since we depend on these resources, it is our responsibility to rein in and control our greed. It is essential that religious leaders not only teach about individual moral issues but global issues as well and provide moral guidance on environmental stewardship. Spiritual teachers can evoke an emotional feeling and commitment, encouraging us to change so we come to see that the environment is not external but in our minds as well.”

A third question asked about meditative practices that can help dissolve the distinction between self and other, inside and outside. The Karmapa responded, “There are a number of meditation practices to dissolve this false boundary. One is contemplating the equality of self and other. We create an empathetic relation by recognizing that just as I wish to be happy, so do others. We are all the same. Once we see this, then we have to put it into practice.” He also mentioned the practice of sending and receiving that works with the breath. In applying this to environmental awareness, he suggested, “We could think about how trees breathe out the oxygen we need to breathe in and we breathe out the carbon dioxide that trees take in. We can contemplate how our breathing is interconnected with these things that grow. We are two parts of one whole system.”

A final question asked how students can organize themselves to do something practical. The Karmapa advised, “There are several things we can do—the usual things like demonstrations of various types—but fundamentally each of us has to start with ourselves, the only solid basis for the type of courage it will take to make these changes. We have to make changes in our life with a courage that can’t be taken away from us and this way we can have a long career. If we have not changed ourselves, we fuel ourselves with expectations and get burned out when others do not change.” So change begins from within, and the Karmapa further advised that working in groups and giving each other support is a good way to promote change and sustain our efforts.