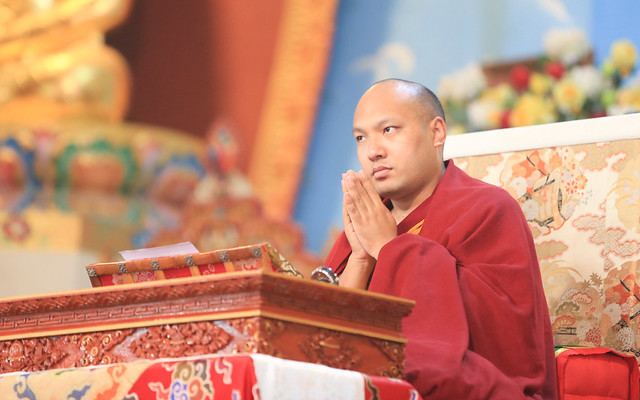

Today the Karmapa began with the section in the Ornament of Precious Liberation on the eight benefits of aspirational bodhichitta. The first benefit is that aspirational bodhichitta is the gateway into the mahayana. Whether or not we are a mahayana practitioner depends on having aspirational bodhichitta in our being. It is what distinguishes the mahayana path or indicates a truly compassionate person.

And what makes compassion great is the scope of our resolve: we seek to benefit all infinite living beings without exception, to bring them happiness and free them of suffering. If we can shoulder this responsibility, our compassion is great; if not, we are just repeating empty words.

Aspirational bodhichitta is also the very basis for all the training of a bodhisattva. It is so powerful that if we can maintain it, we can even retake full ordination vows we have broken. Just keeping the vows of individual liberation (pratimoksha), however, would not allow us to retake the full ordination vows in a perfect way. From among four powers for repairing misdeeds, aspirational bodhichitta is the greatest in terms of the power of the support. Aspirational bodhichitta is also the seed that becomes the stable root for buddhahood.

Aspirational bodhichitta brings immeasurable merit, and on the other hand, the consequences of abandoning it are huge: bringing suffering, a reduced capacity to benefit others, and delay in achieving full awakening. The Karmapa added that he read in an instruction manual that if aspirational bodhichitta deteriorates, the negative consequences are as vast as space, so there are both great dangers and great benefits.

The tenth and final topic in this chapter, “The Proper Adoption of Bodhichitta,” treats the causes for losing the bodhichitta that we have cultivated. Since this is a crucial point for practice, the Karmapa spent some time discussing it. “Bodhichitta is lost when we give up on a living being,” the Karmapa said. “This commitment not to turn away from others is the most important one for the bodhisattva vow.” Bodhisattvas are dedicated to helping others, but if they turn away from other living beings, how could they possibly bring them benefit?

The Karmapa then added, “How do we measure or define what it is to give up on another?” In his commentary on Atisha’s Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment, the Fourth Gyaltsap Rinpoche (Drakpa Döndrup, 1550-1617) writes that giving up on living beings means that your mind is not able to rejoice for them. The Kadampa spiritual friend Potowa states that if for any particular reason we get annoyed with someone, that means losing our affection and compassion for that living being. The Karmapa then gave an extreme example of abandoning another, telling of two worldly people fighting and saying to each other, “In this life we can never be together, and when we die, we’ll be buried in separate cemeteries as well.” On a different scale, he gave the example of thinking, “If an opportunity comes, I will not help this person.” Or “If there is a chance to remove a fault or an obstacle for this person, I will not do it.” These illustrate losing our affection and giving up on someone.

In his extensive explanation of the preliminary practices, Jamgön Kongtrul Lodrö Thaye quotes Puchungwa, who speaks of three conditions that need to come together for losing the vow: 1) The other has to be suffering; 2) there is no one to help them; and 3) we have the ability to protect or help them. When all three of these are present and we do not help, that is abandoning the bodhisattva vow. The spiritual friend Chen Ngawa said that if we think that there is no way that we could get along with another person, that we could never be in harmony, this is giving up on them.

Continuing to cite other authors, the Karmapa spoke of the Kadampa master Shonnu Gyechok (or Könchok Sumgyi Bang), who was also a disciple of Je Tsongkhapa and wrote the most extensive commentary in Tibetan on the Lamp for the Path to Enlightenment. He wrote that if we think that the louse larva is so small and insignificant that it makes no difference if we kill it, that is giving up on living beings. We are not valuing their life nor remembering that even this tiny being wishes for pleasure and wants to avoid suffering. A louse and an elephant are different in size but the same in having a life force; simply because one is bigger does not make it more important.

The Karmapa summarized, saying that to give up on living beings and lose our bodhisattva vow does not mean giving up on all of them: giving up on a single being means that we have turned away from our bodhisattva vow. If we are separated from our affection or compassion and think, “Even if I could help this person, I won’t. Even if I could turn away danger for them, I won’t,” we lose the bodhisattva vow.

Atisha spoke of three types of not giving up on living beings: 1) Those who have helped us; 2) those who harm us; 3) and not giving up on a being who is actually suffering. The first type is the easiest to maintain, for we have gratitude toward those who have helped us. The second is more difficult, and we need to understand that we are linked to those who harm us through the ripening of our karma. Here, of course, the Karmapa noted, we must believe in karma as cause and effect: If we harmed someone in the past, the result is that that we will be harmed in the future. That they harmed us is not good, but we need to consider the whole human being, and as such, this person wishes for happiness and wants to avoid suffering just like us, so we should not lose our sense of respect and stop valuing them. Atisha’s third type is not giving up on a being that is actually suffering. When we see suffering, we should think of its cause—karma and the various afflictions—and this naturally brings up great compassion and love within us. Not giving up on them, we think, “Wouldn’t it be great if they were freed of this suffering and its cause?”

The Karmapa emphasized that training in not giving up on any living being is mentioned first as it provides the basis for the vow of aspirational bodhichitta. He then brought in the First Karmapa’s statement that even if someone is going to harm your body or diminish your possessions, if you continue to help and care for them without despair or sadness, that is not giving up on a living being. We need real courage to do this and let go of our own benefit to think of others first. If we are focused on our own success or attached to our body or possessions, it is difficult to continually help others, so we need to loosen our clinging to ourselves.

The Karmapa then cited an example from the Kadampa teachings on the stages of the path: Your house catches on fire and you immediately start to flee outside. At the threshold of the front door, when you have one foot out and one foot in, you remember the other people left behind and think, “Saving myself is not enough. There are others I must protect,” and so you return inside to help. Great bodhisattvas think like this but for ordinary people, it is difficult due to their fixation on themselves. To remedy this, we need to do all we can to develop the realization that ourselves and others are equal, in that we both have the feelings of pleasure and pain. With this remedy and vivid example of what it means not to turn away from others, the Karmapa concluded his talk on the Ornament of Precious Liberation for this morning.