July 25, 2016 – Sidhbari, HP, India

For over twenty years now university students have been coming to Dharamshala under the auspices of the Gurukul program to receive an extended introduction to Tibetan spirituality and culture. They live in nunneries and monasteries as well as meeting with Tibetan artists and activists. The students learn what it takes to leave a homeland, come to a new country, and start from scratch, all the while working for the welfare of the country left behind. They hear about Buddhist philosophy and about the Tibetan government, and NGOs.

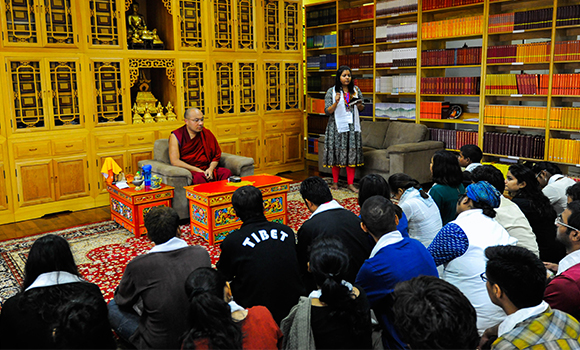

They also watched the Lion’s Roar, a film about the Sixteenth Karmapa. On their last day of participating in interactive sessions, the students came to visit the Seventeenth Gyalwang Karmapa and ask him their questions. First His Holiness was requested to relate something of his life story, and then he opened the floor to the students’ queries.

The first one asked: Since the Karmapa was known for supporting the conservation of nature and wildlife, could he give some tips on how to have more love and compassion for them?

His Holiness responded, “I was born in a remote place and lived close to nature, so I could see its beauty. Our life style then was very traditional and we lived in harmony with nature. This chance to be close to nature and experience it firsthand is the reason I felt motivated to protect the environment and its wildlife.”

This kind of childhood experience, he noted, it very precious and important. Many people have been born in the city and continue to live there so they do not have the experience of being in touch with nature. It would be good for them to spend more time out in the natural world.

He further suggested that we should also understand the interdependent relationship between ourselves and nature, and how important it is for us and all living beings. If we can do this, then slowly we will increase our love and gratitude to nature.

One young woman commented, “Before I did not know the physical size of Tibet. I thought it was a small country, but actually it’s really big. I was not aware of all the natural resources in Tibet some of which can be used for many things. Tibet is also the central waterpower in Asia. Now we’re learning how important it is to conserve all these natural resources.” His Holiness agreed with her.

One of the leaders of the group said, “One might feel that Tibetans in exile are quite happy and everything is going well, but we do not see what is going on in Tibet.”

His Holiness responded that there is a big difference between the Tibet he knew when living there and today’s Tibet. Lhasa has become two times bigger than before. “Many friends told me,” he said, “when you visit Lhasa, you get the feeling of being in a modern Chinese city. It does not seem like Tibet. When I heard this, I thought that on one hand maybe it is good, but on the other, people come to see Lhasa because they want to see Tibet not a Chinese city.”

He added that this transformation makes him wonder what other things will change in the future. “Change is happening very quickly,” he remarked, “and as things develop, people have more desires and more money. They want to build bigger houses, more roads, and buy more cars. Lhasa now has lots of traffic jams. Many things have changed. I have the feeling if I could come back to Tibet, I wouldn’t be able to see the natural and pure Tibet I once knew.”

Another student asked why the Tibetans did not use violence, since it’s a question of their survival.

The Karmapa responded that in our contemporary world, violence seems to be nonstop. In the media we can hear bad news every day. “Recently in Afghanistan there was a bomb that killed 80 innocent people. We do not want to see this kind of thing happening.” He continued, “Even when Tibet is in a critical, difficult situation, I think we still have the option of different avenues of approach and different choices. It is not that we have to take a certain position and have only one single choice. I don’t see it like that.”

Another questioner queried: In Tibet there have been 144 instances of self-immolations. In Xinjiang, the people are killing the Chinese. So in one place, they are doing violence to themselves and in another, violence to others. Still in Buddhist philosophy, self-immolations are considered a form of violence. What do you think?

The Karmapa replied that he had already made several appeals to people not to self-immolate. “Maybe I’m the only person saying this,” he remarked, “and I’m a little bit worried, but I can’t bear this so I must speak. We have high number of people who have self-immolated, but all these deaths have not brought the desired result. Internationally, no country really cares about them, and it is such a waste of this precious life. In general the Tibetan population is small; each and every person is valuable and needs to survive for the cause of Tibet. That is why I have made an appeal several times, saying that this is not a good choice.”

Sometimes the Tibetans in Tibet do not understand the international situation, the Karmapa explained, because they have not received correct information. “They have the mistaken idea that if they do something, people outside Tibet will like and support them. Or they think that the international community will take some action or challenge what is happening in Tibet. But this comes close to being just an illusion. They should understand that if they continue the immolations, they are wasting their lives. It is also not good for Tibet or for their family. These are the reasons why I think they should choose another method. There are some people, for example, who are doing a very good job. They are studying, maybe by themselves, and getting a good education, so they can serve their community. We should adopt these more realistic ways.”

The next person asked the Karmapa about his stand on Tibet being autonomous or independent. He replied, “The leadership of His Holiness the Dalai Lama is very important. We all need to agree and support his leadership, because everyone can come together under his guidance. Unity has the greatest power. If we become divided into parts, I do not think we will get any result either for independence or the Middle Way. That is why I think the two sides need to understand each other. They cannot just hold on to their own view, but need to take in the larger picture.”

The next question concerned the degradation of the environment and the role of governments.

The Karmapa answered that many governments do not want to believe that the environment is a critical issue. They rely on oil and want to continue their economic development, so they are reluctant to make changes. In the short term, he remarked you can avoid these issues, but in the long term you cannot. “Scientists say that human greed is too powerful, and even if we had 3 or 4 planet earths, it would not be enough. Human greed has no limitation, but our natural resources do. This is the problem.”

“Will you be the next Dalai Lama?” asked the next questioner.

The Karmapa replied that he should create an official document to answer this question as so many people ask it and the media is repeating it, too. “I cannot be the next Dalai Lama,” the Karmapa stated. “The next Dalai Lama will be the Fifteenth Dalai Lama, not me.” He continued, “Also you need to understand that I’ve already become the Karmapa, and being the Karmapa is enough. It is a heavy responsibility and I cannot carry more than that.”

People are also saying, he continued, that he would do the Dalai Lama’s work of benefiting all Tibetans after His Holiness passed away. But there is no need to wait until then for him to engage in benefiting the Tibetans. “It is not like that,” he explained. “Then it almost becomes like the Chinese who are waiting for His Holiness to pass away, and then they think the whole Tibetan issue will die out. They do not recognize that there are existing Tibetan issues but think it’s only the issue of the Dalai Lama. This is not true. After His Holiness passes away, the situation will be come more difficult, for no one will be able to control it.”

“In my case,” the Karmapa explained, “even if His Holiness passes away, I will serve. It is not because I would receive another position; it is because I am one of the very important lamas in Tibet, maybe the longest reincarnated lama in Tibetan history. That is why I have some responsibility, not just for my own lineage but also for the general welfare of the Tibetan people. I take that on that even now. There is no need to wait until His Holiness passes away to start a program or make plans. I will do that right now.”

In speaking of the future, the Karmapa noted, “We already have political leaders, who are elected by the people. They will take care of the political part of Tibetan life. For the religious part, each lineage has their own leaders, and I do not think someone who is not the Dalai Lama can be the leader for all these spiritual leaders. That is not realistic.”

On a more personal level, the Karmapa said, “Even the Fifteenth Dalai Lama could not. It is difficult to earn the kind of respect that is given to the Dalai Lama with all his vast activities. The Fifteenth will be under a lot of pressure, as people will expect so much of him, saying, ‘You should be like the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, who was like this and did that.’ I think it would be very difficult to bear this kind of pressure. The expectation and the reality are very different. I know this from my own experience.”

The following question touched on the Tibetans in exile. Have they done their part for the Tibetan cause?

The Karmapa noted that 2018 is the sixtieth anniversary of the Tibetans being in exile. It is difficult to satisfy all needs, he said, but “I think we have done a lot. For any Tibetan coming from Tibet, we provide an education and a place to stay. Not many refuge communities can provide these facilities. Even so, I think many people are not satisfied, even me. We will do better, but sometimes it’s not easy. India society moves at a slower pace. Some Indian friends tell me that India is like an elephant. ‘Why?’ I asked. ‘Because elephants move very slowly and they are powerful,’ they replied.”

The Karmapa commented, “I think we Tibetans are moving a bit slowly, too. Tibetans tend to think of themselves as refugees and get stuck there, thinking, ‘We cannot do much because we are refugees. We have to be satisfied with less.’ Maybe we need to change this kind of attitude, because young people like development and need new things. This why many people have left the Tibetan settlements and moved to different parts of the world. They do not want to stay here. Others are going back to Tibet, and the flow of Tibetans from Tibet has almost been stopped, so it could be that after 10 or 20 years, there will not be much of a refugee community left in India.”

Reprising his thoughts on the slowness of change, the Karmapa observed, “Sometimes I think we should change slowly. Even if the change is a good thing, we may need time. In the past I have encouraged people to stop eating meat, but I do not like to order people to do something. People need to clearly understand the reason why they are doing something; maybe they can come to experience why not eating meat is meaningful and then stop. Otherwise, it is not so meaningful; it is good but not perfect, so slowly is better here.”

The last question asked the Karmapa about what inspired him and how he found time to pursue his artistic interests.

The Karmapa responded that some people think since he is the Karmapa, he does many different things. He commented, “If I am diligent enough, maybe I will become better at them. Sometimes I make paintings, poems, dramas, songs, music, or graphic designs. Usually I do not see myself as a high lama like the Karmapa. I see myself as a servant, and that is why I do a lot of things on my own. It is tiring and not easy but I take this as an opportunity. I do not think that since I received the name of the Karmapa, it means I am a great person. It is not like that. Having this name means that I have the opportunity to serve people. Thank you.”

[During this dialogue, the Karmapa spoke in English, which was slightly edited.]