April 30, 2017 – Sarah College of Higher Tibetan Studies, Dharamshala, Kangra, HP, India

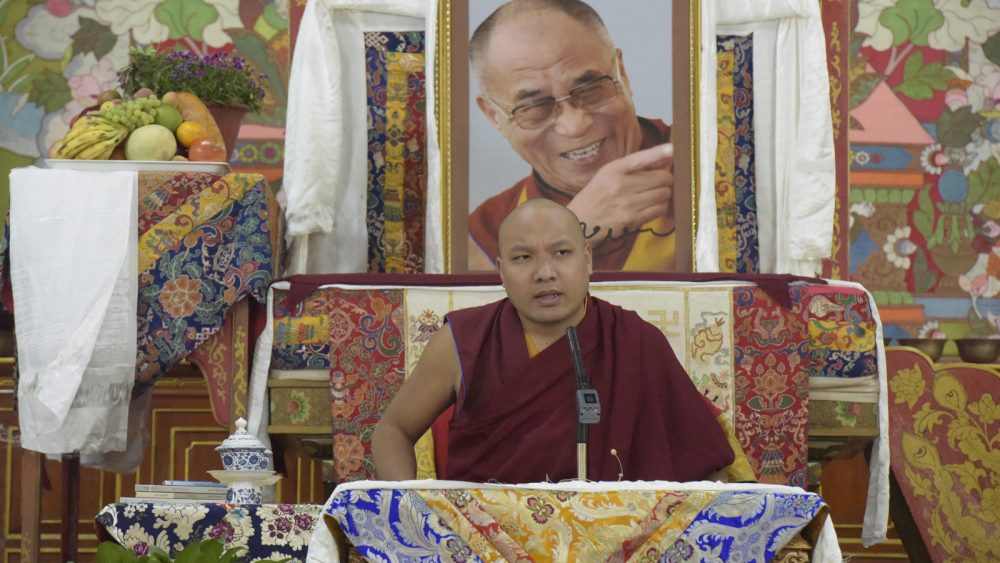

The Gyalwang Karmapa’s car passed by ordained and lay students who stood along the tree-lined road leading to Sarah College. After a brief visit to the college office, he was invited into the main hall where he was offered a mandala and the three representations of body, speech, and mind. As the Chief Guest, the Karmapa had come to confer, along with Kalon Karma Gelek Yuthok, certificates to the Lobpon graduating students, the Uma Rabjampa and the Parchin Rabjampa students from Institute of Buddhist Dialectics, which shared this convocation ceremony with Sarah College.

Welcoming everyone, the Karmapa noted that he’d had quite a bit of experience attending functions at universities, both in India and abroad, yet he felt a special connection with Sarah College that made him especially happy to participate in this ceremony. For special greetings, the Karmapa singled out the students who had studied the major texts of all the four main traditions in Tibet, and he also gave a special greetings to the lay women who had completed their studies for Uma Rabjampa and Parchin Rabjampa: “Carrying out a policy of not differentiating between the ordained and lay Sangha,” the Karmapa observed, “Sarah College has opened the opportunity for everyone to study Dharma, including lay women. It is excellent that all women can now study the major texts.”

Turning to the study of the Tibetan language itself, the Karmapa stated, “It is the very root of everything.” “If we look at the texts from Dung Huang,” he continued, “we will see two types of language. One comes from the Buddhist sutras and treatises and the other from historical documents, communications, and correspondence of that particular time. In the traditional Buddhist texts, the style, grammar, and way of expression are quite similar to what we see today. However, the language of the historical documents, official communications, and letters have undergone change and exhibit a different style, grammar, and ways of expression.”

“There is a big gap between these two types of language,” he explained, “and the colloquial gives us the most difficulty when we come to study Tibetan. This is often the case with other languages as well. When I studied Korean, I was told ‘You write it like this, but you have to learn the colloquial differently.’ This divergence between literary and spoken languages is similar to Tibetan. The pronunciation of colloquial Tibetan changed over time as letters became corrupted and left out. This situation makes it hard to discover what the actual pronunciation was.

“For example, in the Tibetan language spoken in Eastern Tibet, we say ‘Tering mida katsu lep du?’ (‘How many people came today?’) What is unusual here is ‘mida’: mi clearly means ‘people,’ but why is the da there? It turns out that this is a corrupted form of rta (horse) since in the olden days, people (mi) always arrived on a horse (rta), so they were inseparable. Over the years, the pronunciation had shifted from ta to da. However, no matter what the pronunciation might be, you would always write it the same (mi rta).”

The Karmapa then brought up Kadampa texts that contain the teachings of their masters. “They are written in the colloquial language of Central Tibet, so with these records, we can hear the actual pronunciation of a language that was probably widespread at the time.” The Karmapa also remarked, “When you are reading literary Tibetan, you do not pay much attention to the language. It just goes on by. But when you are reading colloquial, the feeling is different, and you naturally take an interest in what is being said.”

“How can the great gap between written and colloquial languages be lessened?” the Karmapa asked. “Usually Tibetans who have gone to school still cannot read literary Tibetan. If you give them a treatise, or even a normal book to read, it’s not certain they could understand. On the other hand, if you give such texts in their own languages to an educated foreigner or Chinese, most of them would comprehend. For this reason it is essential to preserve our spoken and written Tibetan. Many people should reflect on this situation and do research.”

The Karmapa observed that Sarah College has emphasized the study of Tibetan language and culture, so people with these interests have come here to study Tibetan Dharma, language, history, and the Buddhist sciences, such as grammar and poetry. “It seems, however,” the Karmapa continued, “That the way of thinking and behavior has changed somewhat. In general, devotion can move in two directions: if it goes off in error, it becomes blind faith; if it goes well, it becomes a deep, abiding faith.” “Before there seemed to be a strong belief among the students,’ he observed, “but now one can see that their behavior has changed. It is difficult to say why and yet it is important that we pay attention to this.”

Shifting to the topic of Tibet’s future, the Karmapa warned, “In Tibet, the numbers of those opposed to Dharma and to Tibetan cultural traditions are gradually increasing. On the one hand, this is happening all over the world, so it is not surprising. However, we Tibetans have arrived at a critical juncture, when it is of the utmost importance that all of us work together and keep our minds in harmony. Of course, people have their own way of thinking and philosophy, but if this leads to great social disturbances and entrenched opposition, the Tibetan society will be dismantled and destroyed.

“It is perfectly all right to have our own view and position on things. These, however, are not about making a big impression on others; rather, we should seek out our commonalities. Since we live in a precarious time, it is crucial that we cooperate and keep our relations compatible. If you look from the outside, we seem to be a powerful people but within our society, there are clashing views and heated arguments based on the hardened positions we have taken. In such a situation, it will be difficult for Tibetans to ever rise up again.”

“There are different political positions,” the Karmapa observed, “diverse ways of holding cultural traditions, and a variety of religious traditions. On the one hand, these create a rich social fabric as well as fields for discussion and exchange of thought. However, it is a great mistake if we craft strategies and make plans based on our own particular ideas and for our own personal benefit. This will tear apart our social harmony.”

Speaking of Tibetan customs, the Karmapa commented, “From one perspective, many of our customs could be seen as faulty. However, I do not think it would be a good idea to toss away all the old customs. Tibetans are a bit different from other people. They have a close connection to their customs and traditional ways of doing things, which are in turn deeply related to the philosophy and practice of Buddhism. If we were to eliminate them all, we would be left without our precious jewel, our beautiful ornament, bereft of something we could show to others.”

“Previously we could not stand on our own two feet. Remembering this, we need to look at the culture we have inherited and treasure it. We should maintain it into the future while at the same time, staying in touch with our contemporary world and the discoveries of science. We should study what science has to say. On this basis, the Tibetan people’s heritage, for example the Dharma texts, can become more important and powerful than before. For this to happen, a mind imbued with Dharma and a stable sincerity are essential.”

The Karmapa then addressed another problem he saw in Tibetan society. “Sometimes the preoccupation with politics is too strong in our Tibetan world. People talk about it all the time. Instead, we should be discussing Dharma and our cultural and academic traditions. The Tibetans in Tibet have affection for one another, and you can find instances of true harmony between the three major cultural areas of Tibet. This is different from the situation of my youth when Eastern Tibetans were Eastern Tibetans and Central Tibetans were Central Tibetans and that was that. Tibetans in Tibet are starting to see that they are all the same, have the same flesh and blood and aspirations. They are not always talking and arguing about politics the way Tibetans in India do.”

The Karmapa then advised, “Whatever happens to us, we should face it directly. Up to now the Tibetans in Tibet have sustained their enthusiasm and not become discouraged. We should take them as a role model.” “The Tibetans who came in the beginning, he noted, “had a sincere, straightforward, and wholesome mind that was stable as well, but now people have become hypocritical and deceptive.”

The Karmapa cautioned, “At this critical stage in our history, we need to be very careful, especially since HH the Dalai Lama is moving up in his years, and the population of Tibetans in India is decreasing. Many want to go abroad. I’m told four or five thousand a year make the attempt, and though not all succeed, Tibetans have the aspiration to leave. On the other hand the number of people arriving from Tibet is decreasing.”

The Karmapa concluded with a summary of his advice and a warning. “Tibetans need to be unified in a firm and stable bond. We need to be skillful in maintaining the continuity of our Tibetan Dharma, culture, and society. And we need a stable mind that is permeated by the Dharma. Without this, it will be difficult for us in the future.”

At the end, the Karmapa ended with his congratulations to all those who completed their studies and a special greeting to Taklung Shabdrung Rinpoche, who received his Uma Rabjampa degree.