Mar Ngok Summer Teachings 2022: Day 4

His Holiness warmly greeted the teachers, the geshes, the tulkus, the community of sangha members, and all those listening by way of the internet to this fourth day of teachings. He announced that he would be speaking about three topics during this session: i) what the sangha is and how it originated; ii) the origination of the monasteries; and iii) how the Vinaya originated and how the rules were made.

The non-observance of the Vinaya and the origin of the Vinaya

In previous sessions, His Holiness spoke of the meaning of the word “vinaya”, and thus today he began by speaking of its origins. He explained that the Vinaya originated because people did not observe it. What is meant by this? The 20th-century English female scholar I.B. Horner, who was a very skilled historian and researcher of Indian Studies, felt that according to the Vinaya, many bhikshus and bhiksunis were careless, lazy, or lustful. They liked luxury and they liked enjoying themselves. Some also created disharmony amongst members of the sangha community. Yet thinking there were only bhikshus and bhikshunis who brought disgrace to and corrupted the sangha or who had great faults would be to misunderstand the situation that existed at the time of the Buddha. Certainly in the sangha there were people with rough, rowdy or bad behaviour; these events are recorded. However, we should note that in the Vinaya there are only descriptions of incidents of people who behaved badly and we speak about these misbehaving bhikshus and bhikshunis over and over again. Those who behaved well were not recorded in the Vinaya! To think that all bhikshus and bhikshunis at that time were rascals would be to ignore and diminish the many bhikshus and bhikshunis who were behaving well, who were upright and faithful students of the Buddha, and who had gentle characters. There were many sangha members who were embarrassed or ashamed to see their dharma brothers and sisters behaving badly; they could not bear it and found these situations difficult. His Holiness advised listeners to consider this. His Holiness continued by reminding us that corrupt behaviour could happen at any time and that there has continually been people with bad behaviour since the time of the Buddha.

From Horner’s perspective, we actually need to say thank you to all those bhikshus and bhikshunis who behaved badly. Because of them, we have the pratimoksha. The Buddha made rules as a result of these incidents. Thus these badly behaved monastics left us this jewel of the Pratimoksha as an inheritance. If everyone had been upright, well-behaved, careful, chaste, and diligent, there would be no reason for the Pratimoksha to exist. Looking at all the different incidents described in the Vinaya, the Vinaya rules, and the Pratimoksha allows us to have an idea of the historical traditions of that era. From a historian’s perspective, these records are extremely important.

His Holiness proceeded to speak about the wearing of robes. According to the Tibetan Vinaya scriptures, the earliest sangha was the Great Group of Five. Because of the Dharma they gained realization and the noble sangha began. These bhikshus originally wore their robes as they had before, that is to say how merchants and rich people wore their robes. Local householders who had faith in them saw them and thought this was strange. His Holiness elaborated by explaining that lower robes were once square pieces of fabric or cloth that one would wear by tying a knot around oneself. In Tibet during later times, instead of being rectangular pieces of fabric, robes were sewn into a tube shape although they could originally be made according to the Vinaya. Some robes were not sewn entirely and there were empty parts. In any case, local householders remarked that the Great Group of Five folded, fastened, and tied the knot of their robes exactly in the same manner as rich people and merchants. When this was mentioned to the Buddha, he told the Group of Five that from that day onwards, they would need to wear the robes wrapped around them in a way where it was even, with no longer or higher parts than others. “Wrap the robe around you” was probably the first rule the Buddha made.

In the 13th year after the Buddha awakened to Buddhahood, Bhikshu Bhadra engaged in sexual intercourse. Consequently, the first rule of defeat was made. Here we can see that many of the important rules for the sangha were not made in its initial years but were made quite a few years later. At the time of the Buddha, generally there were customs or traditions of wandering mendicants that sangha members would have naturally kept. Therefore the Buddha hadn’t needed to make rules about the four defeats until people started committing them. Later, the Gang of Six badly behaved bhikshus and the Gang of Thirteen badly behaved bhiksunis appeared and did various things so it became necessary to make quite a few different rules.

What is a monastic?

From one perspective, His Holiness said, these badly-behaved bhikshus and bhiksunis might have done some things that we present-day monastics resent. We may think “if they hadn’t behaved so badly there wouldn’t be so many rules and we wouldn’t have so many precepts to keep”. It may therefore be easy to resent and blame them, and to complain about them. On the other hand, we can appreciate that, because of their bad behaviour, there exists a difference between householders and monastics. Here, His Holiness began speaking about what distinguishes monastics from the lay community. According to the Eighth Karmapa Mikyo Dorje, distinguishing between the two communities is not always easy. Can we say that monastics know the Dharma but lay people do not? No, because in fact many lay people know the scriptures, sutras and tantras. Is it the wearing of robes that distinguishes monastics from householders? No, because in this degenerate time many lay people wear robes as well. When you look at them, you might even think they are monastics when they are in fact householders. What about reciting prayers? Do monastics recite prayers whereas lay people do not? No, it is not this either that distinguishes householders from monastics as many laypeople engage in reciting prayers and meditating. Therefore, we must ask what it is we mean by “monastic”.

His Holiness defined a monastic as someone who has turned his or her mind away from the sensory pleasures of form, sound, scent, taste, and touch. He continued by saying the a monastic has few desires and is content, satisfied with even meagre amounts of food and clothing. Monastics are those who are careful in holding their bodies, speech, and minds with mindfulness and awareness. Knowing that misdeeds and non-virtues are easily committed, they act in a similar way to caring for a wound. If you touch a wound or hit it with something sharp, it hurts so you are careful. Monastics worry about committing misdeeds and they try to avoid them. They give up envying others and looking for their faults. Being a monastic also means taming the afflictions as much as you can, in particular the pride in your mind. It means that the conduct of body, speech, and mind is so fine and so good that when everyone — including gods and humans — see you they say you are like a venerable person, a master, a spiritual friend. They may think, “If I don’t pay homage to you to whom will I pay homage? If I don’t go for refuge to you, then to whom?” They may request, “Please grant your blessings so that I may be like you.” You inspire them because they can place their hopes in you. This is what we call a venerable person, a monastic, a practitioner.

We give the name “Dharma practitioner” to various types of people but it’s possible that monastics who are like lay people are in fact worse than lay people. For this reason, the main distinction between monastics and lay people is not made in terms of the view. Instead, it is made in terms of the fine conduct of the Vinaya. That there were badly-behaved bhikshus and bhikshunis therefore worked out well for us. In the Mahayana Sutras, it is even said that Udayi (one of the Gang of Six) and Devadatta were emanations of the Buddha. From a historical perspective it seems inappropriate to say they were emanations, but from the point of view of philosophy and practice, His Holiness said it is very beneficial to say so.

The meaning of Pratimoksha

Showing the first slide of his presentation, His Holiness explained that the Pratimoksha Sutra (Prātimokṣa Sūtra), or the Sutra of Individual Liberation, contains 250+ rules of the Vinaya but does not teach the rituals of actions that the sangha must perform. He then offered three meanings of the term Pratimoksha (Pali: pātimokkha), as given in a commentary by Vimalamitra.

In the first, “prati-” means individual, that is our own individual, personal selves. “-moksha” means achieving liberation. Therefore when put together, pratimoksha means individual or personal liberation. An individual liberates him- or herself from the lower realms and from samsara but cannot protect others from them.

For the second meaning, “prati-” refers to first or initial, and “-moksha” again means liberation. This means that in the first moment of receiving the vows, you are liberated from the faults of previously having wrong vows. For example, if you were once a butcher, it means that you had decided and were committed to killing animals. This is what is called a wrong vow. Regardless of whether you actually killed an animal or not, you had a commitment to do so. But the instant one takes the pratimoksha vows, one is naturally and automatically liberated from once having wrong vows.

Third, “prati-” can refer to “means”. Therefore, the third meaning of pratimoksha can be the methods or the means of liberation.

The categories of downfalls and their explanations

Continuing with the second slide, His Holiness taught about the categories of downfalls. The Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya scriptures translated into Tibetan speak of the “five categories of downfalls”. In contrast, the Pali Vinaya divides all precepts into eight categories. They are:

- ཕམ་པར་གྱུར་པའི་ཆོས། Defeats (Pali: pārājikā dhammā; Skt. pārājikā dharmāḥ). All the Vinayas say there are four defeats for bhikshus.

- དགེ་འདུན་ལྷག་མའི་ཆོས། Sangha remainders (Pali: saṃghādisesā dhammā or saṃghadisesa dhamma; Skt. saṃghāvaśeṣā dharmāḥ). In all the vinayas, there are thirteen for bhikshus.

- མ་ངེས་པའི་ཆོས། Indefinite dharmas (Pali: aniyatā dhammā; Skt. aniyatau dharmau). Even though here these are presented as a separate category, in our Tibetan tradition, these are not considered downfalls. Rather, they are situational defeats. All the Vinayas say there are two for bhikshus. However, they are not mentioned in the “Sūtra Requested by Upāli” or the “Sūtra of the Five Dharmas of a Bhikṣu.”

- སྤང་པའི་ལྟུང་བྱེད་ཀྱི་ཆོས། Downfalls with forfeiture (Pali: nissaggiyā pācittiyā dhammā; Skt niḥsargikāḥ pātayantikā dharmāḥ). In all vinayas, there are thirty for bhikshus.

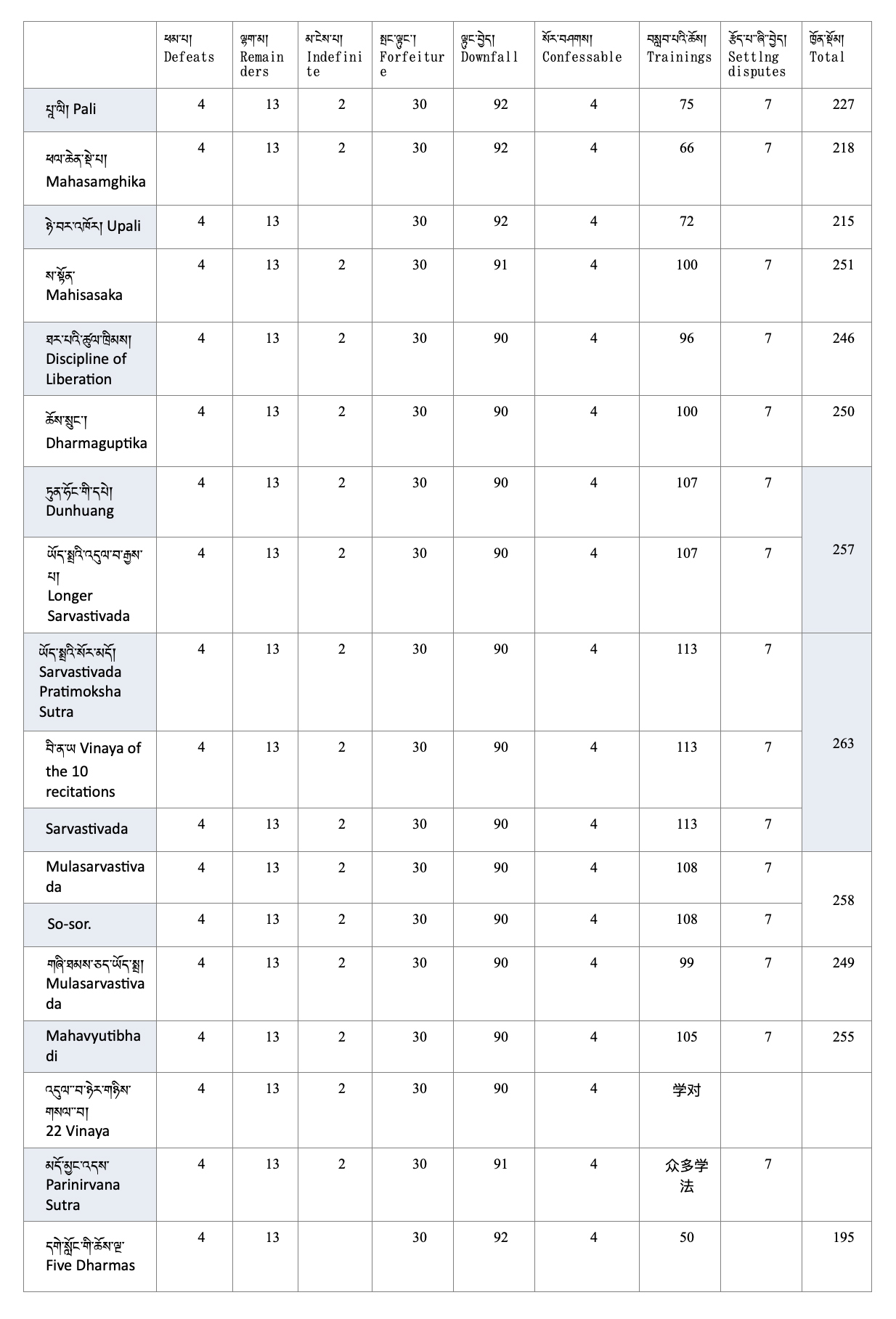

- ལྟུང་བྱེད་ཀྱི་ཆོས། Downfalls (Pali: pācittiyā dhammā, Skt: pātayantikā dharmāḥ). Here there are different totals in three traditions. The first which is from the Pāli canon, the Mahāsāṃghika the “Sūtra of Upāli’s Questions,” and the “Sūtra of the Bhikṣu’s Five Dharmas,” has 92 downfalls. The second, from the Dharmagupta, Sarvāstivāda, the “Clarification of the Vinaya,” and the “ Sūtra of Liberation,” has 91 downfalls. In practice in the Tibetan Mūlasarvāstivāda tradition, we say there are 90 downfalls. You’ll note in the table below it says there are 91 in the Mūlasarvāstivāda, so we need to investigate whether it is mistaken. The difference in one or two downfalls might also be explained because the downfalls of destroying seeds and growing plants are combined as one rule in the Mūlasarvāstivāda but divided into two in other schools.

- སོ་སོར་བཤགས་པར་བྱ་བའི་ཆོས། Confessable dharmas (Pali: pāṭidesanīyā dhammā; Skt. prātideśanīyā dḥārmāḥ). In all the vinayas, there are four for bhikshus.

- བསླབ་པའི་ཆོས་མང་པོ། Numerous training dharmas (Pali: sekhiyā dhammā; Skt. saṃbahulāḥ śaikṣā dharmāḥ). These are what we call the minor offenses. All the different vinayas have different numbers. The Pali Vinaya has 75, the Mahāsāṃghika has 66, the “Sūtra of Upāli’s Questions” has 72, and the Mahīśāsaka and Dharmaguptika have 100. The Prātimokṣa Sūtra found in Dunhuang has 107. The Mūlasarvāstivāda and the Chinese have 96. The Tibetan translation and Sanskrit manuscripts have 108, and so forth. The Tibetan translations of the Mūlasarvāstivāda have 112 but in the table 108 is recorded, so we must check whether there is some mistake.

- རྩོད་པ་ཞི་བར་བྱེད་པའི་ཆོས། Dharmas for settling disputes (Pali: adhikaraṇasamathā dhammā; Skt. adhikaraṇaśamathā dharmāḥ). All the vinayas include seven for bhikshus. However, they are not mentioned in the “Sūtra of Upāli’s Questions,” “Clarifying Twenty-two Vinayas,” or the “Five Dharmas of a Bhikṣu.”

18 different Pratimoksha textual sources

His Holiness spoke about the Pratimoksha vows and offered a comparison of the number of precepts in 18 different vinaya textual sources found in various schools extant today. These are the precepts from various traditions, not just the Mūlasarvāstivāda tradition. The texts mentioned are as follows.

1. The Pali “Pātimokkha”: This Pātimokkha is generally accepted to have been passed down from the Theravada (Skt. Sthaviravāda) school.

2. The “Mahāsāṃghika Prātimokṣa Sūtra”: For a long time this was only available in the Chinese tradition but later a Sanskrit text was found. It is from the Mahāsāṃghika school, one of the 18 schools.

3. The Prātimokṣa Sūtra of the Five Scriptures: This contains the full Vinaya or ‘vibhaṅga’, passed down from a Chinese translation. It was passed down from the Mahīśāsaka school.

4. The “Prātimokṣa Sūtra of the Five Scriptures” also contains the full Vinaya and is a Chinese translation. This is the Vinaya passed down from the Dharmaguptaka (Pali: dhammagutta, dhammaguttika) tradition.

5. The “Sūtra of the Discipline of Liberation” only includes the “Prātimokṣa Sūtra” and does not contain the full Vinaya. It is extant only in Chinese translation. It descends from the Kāśyapīya (Pali: Kassapiyā, Kassapikā) school.

The Sarvāstivāda Vinaya

The Sarvāstivāda is one of the 18 original schools. The different vinayas are the same in that they are sarvāstivāda vinayas, but there are different manuscripts.

6. The first is an ancient manuscript of the “Prātimokṣa Sūtra” extracted from the Dunhuang Caves. This is considered to be the earliest translation of the “Prātimokṣa Sūtra” into Chinese.

7. The next is the “Sūtra on the Causes and Conditions of Vinaya” (戒因缘经, Jiè yīnyuán jīng).

8. The “Ten Recitations Vinaya” (Chinese: 十誦律 Shí sòng lǜ) is primarily related to the long vinaya. Translated literally this means the Ten Verses.

9. The next is the“Bhikṣu Prātimokṣa Sūtra” of the Ten Recitations (广律相关戒本 Guǎng lǜ xiāngguān jiè běn).

10. The Sanskrit “Prātimokṣa Sūtra” was found by the Frenchman Paul Pelliot in Xinjiang. It was published in an edition edited by Finot in 1913.

These five scriptures belong to the Sarvāstivāda school. They are different manuscripts of the same school of Vinaya, but in different translations in Sanskrit and Chinese.

The Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya

The Mūlasarvāstivāda Vinaya is one of the 18, or some say 20, different schools of Buddhism. This is the Vinaya we keep in the Tibetan tradition and there are several different manuscripts for this. We are using the following four for the basis of today’s comparison.

11. The Indian scholar A.C. Banerjee discovered an ancient Sanskrit manuscript of the Mūlasarvāstivāda “Prātimokṣa Sūtra”. The manuscript was inside an old stupa located in a region of Kashmir currently administered by Pakistan. This area, called Gilgit, used to be a Tibetan region named Drushe. The region was later lost to Kashmir for a reason unknown to His Holiness. The manuscript was well-preserved and is complete.

12. The Tibetan translation of the Mūlasarvāstivāda “Prātimokṣa Sūtra” is the one in our Tibetan canon and is complete with the full Vinaya.

13. There is also a Chinese translation of the Mūlasarvāstivāda “Prātimokṣa Sūtra”.

14. The “Mahāvyūha” is not a vinaya text but was compiled at the time of the Tibetan emperors. It is like a dictionary that gives a list of different terms and the numbers of precepts in each category.

The next three texts are not actually vinaya texts but they are sutras related to the Vinaya and are therefore connected to today’s topic.

15. “Upāli’s Questions Ascertaining the Vinaya” (Vinayaviniścayopāliparipṛcchā) is extant in Chinese translation. While not a vinaya text, it lists the precepts and the number of precepts in the “Prātimokṣa Sūtra”. The way they are presented here is slightly different than how they are in other vinayas. Some scholars therefore suspect it is probably from another school. It is an important text.

16. “Twenty-two Clear Points About the Vinaya” was translated into Chinese by the master Paramārtha. This is a commentary on the Vinaya from the Sammatīya (Pali, Skt.: Saṃmatīya) school.

17. The next is the “Sūtra of the Five Qualities of a Bhikṣu”, translated into Chinese by the master Dharmadeva.

18. The last is the “Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra”, a Mahayana sutra. All of the precepts of the Prātimokṣa are here so it was also included by the researchers.

His Holiness continued by explaining that in these 18 different manuscripts contain the vinayas of eight schools, which are: the Sri Lankan Theravada; the Mahāsāṃghika; the Mahīśāsaka; the Dharmaguptaka; the Kāśyapīya; the Sarvāstivāda; the Mūlasarvāstivāda; and the Sammatīya (Pali, Skt.: Saṃmatīya). The Mūlasarvāstivāda is similar to the Sarvāstivāda, so if it is not considered as being separate, there would be seven schools. Then by adding “ Upāli’s Questions Ascertaining the Vinaya”, which as previously mentioned presents the precepts differently, to the above schools you could then say there are manuscripts of eight different schools. There are debates about what school it comes from, and there are those who say it probably comes from Mūlasarvāstivāda tradition. Other scholars refute this because when you compare the Mūlasarvāstivāda to the other traditions, it’s a little bit different. In addition, there is the Vinaya from the Mahāsāṃghika school. Other Mahāsāṃghika texts are extremely rare so this Vinaya manuscript is extremely important.

Comparative studies of the Vinaya

What are the differences between these schools in terms of the precepts and the number of precepts they are said to have? There have been several published studies, which His Holiness shows on the next slide.

1. In 1926, the Japanese scholar Dr. Makoto Nagai published a comparative study of different vinaya texts in the periodical “Religious Studies.”

2. Also in 1926, Waldschmidt published a comparative study of the Bhikṣunī Prātimokṣa Sūtras.

3. The Japanese scholar Dr. Tetsuro Watsuji published “The Philosophy of Practice in Original Buddhism” in the periodical “Early Buddhist Philosophy“ in 1927.

4. In 1928, the Japanese scholar Nishimoto Ryuzan published a table comparing the vinayas.

5. The Japanese scholar Akanuma Chizen wrote a textual comparison of the Prātimokṣa Sūtras (波羅提木叉の比較) .

6. In 1940, Akanuma Chizen published 诸部戒本戒条对照表, a correspondence table comparing the precepts of the various Prātimokṣas in detail.

7. In 1955, W. Pachow, a professor from a university in Ceylon, published the results of his comparative research.

Next, His Holiness showed a comparative table based upon research completed by the aforementioned seven scholars and upon Hirakawa Akira’s “Research into the Vinaya Piṭaka .” Akira redid and improved upon six tables with different comparisons to present the following information.

Looking at Akira’s final totals, it seems as though the number of precepts in different schools’ vinayas are completely different. Even within the same tradition there can be different numbers. For example in the Sarvāstivāda there are two different traditions and in the Mūlasarvāstivāda there are three. Therefore, it seems as though it is not definite or certain. His Holiness believed it is for this reason that many modern researchers have said that later generations must have added to the Vinaya precepts or they may have decreased them.

Despite the different total number of precepts, His Holiness emphasized that the overall structure is the same. The most differences are found in the many trainings, also called the list of minor offenses, but differences are slight. In the Mūlasarvāstivāda tradition there are 112, for example. One Japanese scholar says that because the number of precepts is mostly the same, they must have come from the same source. Otherwise most of the precepts would have been different.

His Holiness continued by presenting the information found within the above table. He cautioned that the total numbers of the Mūlasarvāstivāda tradition listed here and those of our practice is different. This is something we need to examine.

According to Hirakawa Akira, in Pali there are 227 precepts for bhikshus and 311 for bhikshunis. In the Dharmaguptika tradition, there are a total of 250 precepts for bhikshus and 380 for bhikshunis. His Holiness added that in the Mūlasarvāstivāda tradition, there are 253 and 364 respectively. Akira also says that there are differing numbers of precepts in the other vinayas, but for the important precepts of the defeats, the remainders, the forfeitures and the downfalls, all of the vinayas are in agreement. This shows that these precepts were clearly determined or formulated in the period of original Buddhism.

In Tibetan Buddhism, it is said in Sakya Pandita’s “Treatise on Three Vows:”

The different schools are all different,

First in taking vows,

In the middle in keeping, restoring,

Reciting the Prātimokṣa,

And in the end in canceling the vows,

So they each refuted each other.

Here, Sakya Pandita is saying in the 18 different schools and their vinayas, nothing is the same in any of them. How vows are taken and kept, how they are restored and so forth, are all completely different. What is prohibited in one is allowed in another.

For His Holiness, when he looks at these 18 different schools he wonders if it is really this way. He explained that it was understandable that Sakya Pandita was this way; during the time of the Tibetan emperors, it is said that translations of the Vinaya other than that of the Mūlasarvāstivāda tradition were prohibited. Whether it was actually prohibited or not needs to be investigated but Sakya Pandita explained that it was so. In any case, there was only the Vinaya of the Mūlasarvāstivāda tradition, but not of any others. Consequently, it was difficult for Tibetan scholars to obtain manuscripts of other schools and to figure out what differences there were. I believe Sakya Pandita was probably following the sayings or the words of older scholars, His Holiness commented. “These days, we’re in a time when we can study and research Buddhism in many different languages. We don’t need to merely rely on hearsay from past. We are able to now do our research by looking at different schools.”

This is important because in the past, we would say that our Mūlasarvāstivāda school was the authoritative one. Now, when we look at all 18 schools, it is difficult to say one is right and the others are wrong, but in the past, the 18 schools had many different disputes and debates. They said to each other, “you’re not the true dharma, you’re not right, but I am.”

Making the point of being unbiased, His Holiness mentioned the example of King Krikin’s dream in which all 18 schools were the same in being true teachings of the Buddha. His Holiness stressed that this is a really crucial point. Lord Atisha was also someone who was different as he took care of the vinayas and the practice of the four schools — they were the four angles of a square, meaning there was no bias for any particular school. At that time, many schools remained in India and yet he was not partisan. Rather, he was able to look at all of the different schools and their texts without bias. It is for this reason that in the Kadampa tradition, we say that he took the whole teachings of the Buddha. He recognized all 18 schools as being the words of the Buddha, correct and true.

By looking at the differences of these 18 schools, we can benefit through understanding what the practices of each school are and then by practicing them properly, the Karmapa suggested.

Creating rules, harmony, and leadership

As some Japanese scholars remind us, each one of the rules was made after a particular incident, that is to say there was an incident and then the Buddha gave a ruling in response to it. When we look at the background story of the vinayas and examine the records of all the incidents in detail (which give the reason why each rule was made), we can understand how the lives of the sangha members in their ‘dwelling places’ and ‘pleasant groves’ changed, how monasteries changed, how the lives of practitioners changed, and what improvements and developments occurred in their lifetime. Similarly, when we look at various rituals of action, the sangha’s method of making internal rules, we can see the development in their livelihood. Basically, the benefit that came from establishing the pratimoksha rules is that the overall livelihood of the sangha became more organized. These rules were not made in a single day; they were added gradually over time and there were more and more precepts. The Prātimokṣa Sūtras were therefore like a collection made over time, not something that was made all at once.

The Buddha did not appoint anyone to be his successor or to be the leader of the sangha after passing away. There were times when disputes occurred between sangha communities in a single place. It could have been that they might not have really looked at each other because they had the same seniority or level. Then there was the danger that a schism would develop and there would be two different schools of the sangha. What was needed to bring harmony to the sangha was to have the sangha’s rituals of actions. This is beneficial because when doing the ritual of action, sangha members had to get together and have a meeting. Although we tend to think about “ritual of action” as coming together to recite, it was not like that. Ritual of action means meeting together to speak and have discussions, and in order to hold a ritual of action, the sangha would have to gather. Sometimes it was not necessary for all sangha members to be present, but when it was, everyone gathered and then they could make decisions by consensus. In the Vinaya tradition, if even one bhikshu objects, you cannot make a decision. Arriving at a consensus is therefore very beneficial for creating harmony within the sangha.

His Holiness then took the opportunity to speak about who had authority and leadership within the sangha during the time of the Buddha. The Indian scholar S.R. Goyal says that during the Buddha’s lifetime, the Buddha was recognized as the main member or leader of the sangha. What is the evidence for this? In order to gather for the rains retreat, going for refuge to the Three Jewels was the first thing one needed to do. If not, one could not enter the sangha community. In order to go for refuge to the Three Jewels, one needed to go for refuge to the Buddha. Naturally, Goyal says, the Buddha became the leader of the sangha. What is meant here by “leader”? At that time in India there were many religious groups. There were differences between the leaders of other groups and the Buddha. Notably, the leaders of other groups were considered supreme within their own group; they made rules for how their communities would lead their lives and for how they progressed about their business. Likewise, they also decided who would uphold their lineage and named their successors. This was the tradition within all the different religious groups at that time in India. For that reason, many people who were not members of the sangha asked who the Buddha’s successor would be. At that time, all the other religions had this custom of the leader appointing their successor. Only the Buddha and his sangha did not.

Returning to the concept of harmony, His Holiness began speaking about the disharmony between the Buddha and Devadatta, who is often referred to as the “mara” (demon) Devadatta. He explained that when he was young, His Holiness thought Devadatta was like a demon and non-human. Instead, it turned out that Devadatta was human just like the Buddha! He was actually the Buddha’s uncle-son, or we can say the Buddha’s cousin. In any case there was a great disharmony between the Buddha and Devadatta because the latter hoped to be appointed as the Buddha’s successor. He also told the Buddha to give him his students and said he would take care of them. The Buddha, however, did not accept this. Not giving his students to Devadatta shows that the sangha community was going down a more democratic path and more democratic traditions. Previously in a royal or monarchical system, the ruler, that is to say an individual, would be in power. In contrast, in a democratic system the collective or the public has the power. For this reason, the Buddha did not accept Devadatta’s proposal.

According to Goyal, when we call the Buddha the Teacher, it means merely the one who gives advice about how to achieve the ultimate nature and what the ultimate nature is. It does not mean the one who gives commands to and exerts authority over the sangha. That is not what the Buddha said he was. This shows that the sangha primarily followed democratic procedures. Likewise, the Buddha said to the sangha, “You must be your own protector” and “You must take the true Dharma to be your protector and refuge.” He also spoke about how you should not go for refuge to some external successor.

(Due to technical difficulties, His Holiness’ teachings ended here, which was earlier than anticipated).