Karma Triyana Dharmachakra, Woodstock, New York

March 26, 2018

To benefit both the living and those who have passed away, the Ocean of Merit Society organized a special Amitabha practice at the Gyalwang Karmapa’s North American Seat, Karma Triyana Dharmachakra, and invited His Holiness to preside. The Ocean of Merit was started by disciples of Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche, who is its guide and advisor. Rinpoche gave the organization its name with the hope that through its various activities, an “ocean of merit” would be accumulated.

For the occasion today, many disciples drove north from the New York area to join together with numerous others who had come from near and far. Early in the morning gusts of wind blew large snowflakes around the courtyard, but the skies cleared as the time for the ceremony neared. During the two and a half hours it was performed, His Holiness sat on his throne in front of a Golden Buddha, the focus of practice in the KTD shrine hall. Before the practice began, people had written the names of those they wished to help on a sheet of paper, and during the practice, they were offered outside to the ritual hearth in the center of the snowy courtyard.

Karmapa and Sangharāma’s connection to Tsurphu

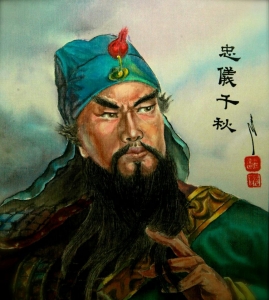

At the time of the lunch break, a separate shrine was arranged in front of the Karmapa to honor Guan Gong, known later as Sangharāma, who is a special protector of Tsurphu Monastery, the Karmapa’s main seat in Tibet. The story is told that Guan Gong was a famous general in China, renown for his loyalty, courage, and integrity. But he had killed many people in battle, so when he passed away, the general became a ghost wandering on Mt. Yuquan. Master Puching took pity on him and gave him teachings, and some three hundred years later, the founder of the Tian Tai school, Zhi Zhe Dahi (538-597), also came to Mt. Yuquan and gave Guan Gong’s spirit not only teachings but refuge vows as well. And so Guan Gong became the Dharma protector Sangharāma, and even now he can be found in Chinese monasteries as a red-faced deity on one side of the shrine.

After the Karmapa came to India, he composed in Tibetan and Chinese a practice for this protector, which has been performed on an annual basis for many years. During an interview on 2005, he explained why he wrote the sadhana. “Recently, there was a wave of national disasters, so I wrote this sadhana of Sangharāma to pacify all obstacles and unfavorable conditions and to increase auspiciousness, peace, and happiness in the world. I also aspired that it would encourage virtue and bodhichitta in beings and enhance the harmony among countries and people.

“When I was young, my teacher for Chinese grammar was very interested the Sanghuo dynasty (220-280 CE) and often told stories from that time, which the I enjoyed hearing. The teacher mentioned that in the past at Tsurphu, offerings were made to this protector, but after the Cultural Revolution, they had stopped. He told me that I should revive this ritual. So when I was fourteen years old, I wrote a short sadhana without thinking very carefully about the words. My teacher was also not satisfied with it, saying that it was too short and that I should write a longer one. Nevertheless, when we performed this short ritual for the first time at Tsurphu, it felt as if the entire area became pure. The sangha played a variety of musical instruments and everyone felt quite happy.

“After I went to India, for a period of time, there were a lot of difficulties, so I did not have time to work further on the sadhana. When I was young, I had seen a lot of dramas about the Sanghuo dynasty, which were produced in China. One night I had a dream that seemed to take place during the Sanghuo period. In the darkness, many soldiers were riding horses, holding high their torches, and shouting as if going to war. Amidst a cluster of tents was a bonfire and I was sitting next to it warming myself. When I looked up, I saw that sitting on a rock in front was Sangharāma. He slowly turned around to look at me and was unbelievably magnificent—much more splendid than what I had seen in books, paintings, or statues.

After this dream, whenever I would see images of Sangharāma, I always felt that they did not look like what I had seen in the dream. Then for various reasons, I began to rewrite the sadhana, intending to complete it in three days, but it ended up taking five. I finished the writing in Varanasi and gave it the title Shenchou Zhongming, “The Sound of the Bell in the Land of the Gods.” Some of my attendants said that the verses were beautiful, so we performed the sadhana right after its completion. As part of the puja, we lit fireworks and everybody enjoyed the show. Friends in Taiwan and China learned that I had written this sadhana, and so I asked everyone to practice it. I have written it to fulfill the wishes of many.”

In response to questions, the Karmapa clarified that he wrote the sadhana so that the practice of Sangharāma could resume at Tsurphu and also for the Chinese people who have faith in this protector. In explaining the meaning of the title, he said. “When I was very young, I had seen a film produced in China called ‘Journey to the West.’ One of the main figures was a monk named Tang San Zang (based on the famous seventh century scholar and traveler, Xuanzang). When he and his entourage returned to China, riding on clouds from India, it is said, they realized they were already in China when they heard the sound of a temple bell, giving them the warm feeling of being at home. I was impressed by that scene and therefore named the sadhana, ‘Sound of the Bell in the Land of the Gods’ with the hope that when Sangharāma hears this practice, that same feeling of warmth would come to him and he would remember his promise to protect Tsurphu.”

Replying to a question about the link between the deity and Tsurphu, the Karmapa answered, “The historical record states that the Fifth Karmapa, Deshin Shekpa (1384-1415), was invited by the Emperor Yongle (1360-1424) to spend three years at his capital. It was during this time that the protector Sangharāma came to Tsurphu, and from then onward, the sadhana was performed at the monastery. In Tibet, the protector was called Karma (related to the Karmapa) Gyalha (Gya means ‘Chinese’ and lha means ‘deity’). The Karmapa added that when he was reading the collected works of the Fifteenth Karmapa, Khakhyab Dorje (1871-1922), he found a short sadhana of this protector and also that the Sixteenth Karmapa, Rigpe Dorje (1924-1981), had recited the sadhana once in India.

Masters in the Geluk and Nyingma lineages have also written sadhanas for this protector, and in Lhasa there was a temple dedicated to him. The Karmapa added that only vegetarian offerings should be made, and that the vow associated with the practice is to keep moral conduct in the world and have the intention to benefit others. “Every time you perform the sadhana there is benefit,” he said.

Since writing the sadhana, the Karmapa continues to develop it, making powerful paintings of the protector, and for this occasion at Karma Triyana Dharmachakra, he composed a beautiful new melody, which he sang in a strong voice as he led the practice.